In the Workshop: What I learned from a decade of fear

16 de octubre, 2013

When you make art about the times you’re living in there is an urgency to speak as things comes up. In that spirit, here are a few notes on the Art and the Issues of one of the new works Aluna is presenting at our festival in February 2014.

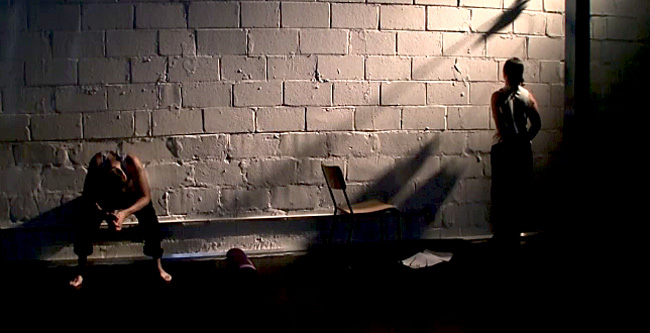

The questions we asked for this piece: What are the effects – on ourselves and our culture – of all that has been done in the name of our security? How has it changed us? What are its unintended consequences? Are the moral and political issues around security, terrorism, and the judgement of others so “hot” that we cannot step back and observe them?

In early 2010 Aluna Theatre began a project (as part of a two-year Residency at the Theatre Centre in Toronto) called The Architecture of Terrorism, based on our observations of how security works on a day-to-day basis in Colombia, in contrast with what is happening in North America in the growing security industry, and its influence on our culture. Our theatre project about current issues was constantly being re-thought under the influence local and world events: since we began, the Toronto G20 street conflicts and mass arrests shook Toronto, both Omar Khadr and the “Toronto 18” have been sentenced, we passed the 10th anniversary of 9/11, and the recent passage of the renewed “Antiterrorism Act” (Bill S-7, the “Combating Terrorism Act”) shortly after the Boston Marathon bombing, showed us all that fear of unknown threats still has a strong hold on the imagination of our government (and yes, on us). Unfortunately, this set of protectionist measures falls hardest on visible minorities, exacerbating issues of ethnic profiling by authorities.

What could we, as theatre-makers, do about this? We make theatre. We speak the language of culture, and perhaps we can re-inject or re-enforce some notions of empathy in this polarizing cultural debate. We want to recapture a personal sense of agency that motivates people to care. We believe that we can do that by moving our audiences to feel responsible for themselves, and for what is done in their name by the authority of government. If our government is interning people based on suspicion rather than facts – which it does – and if they are doing this in the name of our safety – which it claims it is – then we need to feel responsible for that. Let us accept the transparent story: this is for us. The internationally recognized rights of First Nations protestors to free, prior, and informed consent are suspended to end the blockade of an oil pipeline or a mining exploration site on Treaty lands so that we can drive our cars with affordable fuel – this is done for us. Keeping a teenage Omar Khadr in Guantanamo on dubious grounds for ten years without trial, sending Maher Arar to be tortured in Syria, arresting thousands of innocent civilians at the Toronto G20 summit without cause, warning all legitimate migrants to Canada that even if they’ve been here as citizens for 40 years that their citizenship can be revoked based upon suspicion of guilt alone – these are gifts to us, for our safety and our peace of mind.

Did it work? Do you feel safer?

…Alright, that was the first and only angry screed – I promise. It’s a hot topic and we care a lot about it. But to bring our main point to its logical conclusion: the politicians who pass these laws and the police and spies who execute them are also us. Ultimately, if we are to live in a more peaceful society, no one can be outside – there can be no ‘Other’. Our inclusionary principles must apply to politicians and criminals as well as ourselves, lest we turn them into easy villains as well, and avoid the deeper challenges of maintaining our humanity in trying times. Which also made us wonder: How are we just like them – the terrorists and the anti-terrorists alike?

These are the issues in our minds as we build this new show. But how do we turn all that into theatre? Here are two of our strategies:

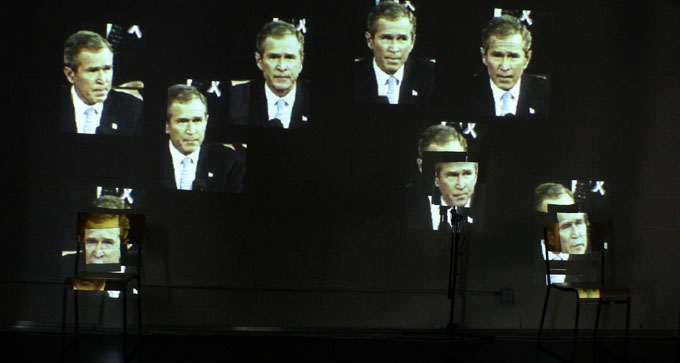

Reappropriating language

As a cultural activity, theatre can redefine perspectives and understandings. Listening to some of the best speech-makers and the rhetorical gestures of nasty militaristic-minded men in government, we realize that they’ve done it, they’ve changed the way we think and the way the world accepts decisions. Or, if you don’t accept that they’ve changed the way we think, they’ve definitely changed the background of how we as a culture react to things: what is acceptable to say in public, what we will pay for our own safety (or our sense of safety), and how we talk about other people who are paying the price for our safety as well.

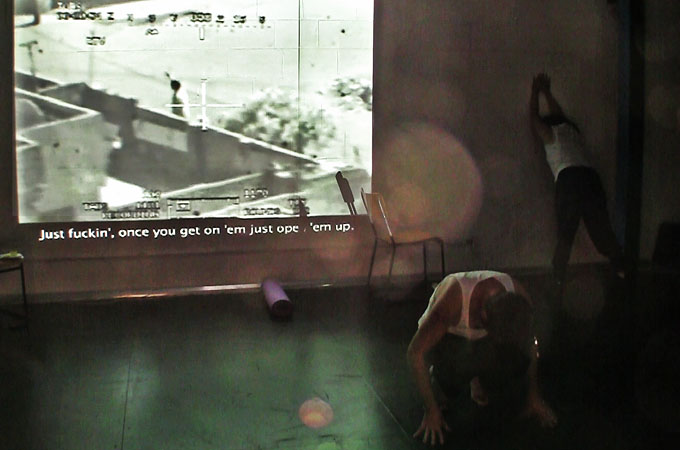

Investigating the image

In a recent article in the Washington Post, art critic Philip Kennicott wonders why images of suffering children in Syria are not galvanizing the public to outrage. Such images have often in the past changed public opinion on issues like famine in Africa, or the Vietnam War. Yet of recent photos he says,

…in many cases, we don’t know who made them and what they depict. All we see are decontextualized cruelty and misery. Cynicism creeps in, and there is a natural tendency to push the images away as a kind of insoluble puzzle.

I understand that feeling: our power to empathize is often burned out. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag writes that there is no way “to ration horror, to keep fresh its ability to shock.” Kennicott concludes,

That is where we are now, in an ecosystem of images and an ecosystem of international decency that have been irremediably polluted.

I immediately wonder if part of our task here is to unpollute images of suffering, to make them powerful again. But perhaps the image itself is not the real issue – it is decontextualization. In other words, lack of real information about what we are seeing. An image is an image, and its emotional impact is an aesthetic one until we learn that we are perhaps connected to this awful event in a more direct way: that we have agency, and therefore, responsibility.